We know very little about “our” GW. According to his headstone, he was born in 1845 in Maryland, a slave state that stayed in the Union, and died in 1917. A 25-year-old “George Washington” appears on the 1870 U.S. Census, living in Frederick. He was a farm laborer; his wife, Carline (or Caroline), kept house. Neither could read or write. They had two small daughters, Mary, 3, and Jane, 5 months.

I doubt whether he or any of his fellow George Washingtons of the 23rd United States Colored Infantry were born with that name. The unit was organized in Arlington, Virginia, within sight of Freedmen’s Village, a camp for people who had escaped slavery. Shedding the name forced on you in bondage and then taking a new one was common practice after one’s emancipation—or self-emancipation, in the case of the Georges and tens of thousands of others.

It’s both fitting and ironic that these men claimed this most American of names. Founding father Washington prospered through the labor of the people he enslaved. “Washington frequently utilized harsh punishment against the enslaved population, including whippings and the threat of particularly taxing work assignments,” says the website of the museum devoted to him, George Washington’s Mt. Vernon. He’d threaten to sell family members of the enslaved to masters in the West Indies. And Washington was, as we know, a man of his word.

Like most “colored” units—there were more than 160—the 23rd was initially kept out of combat. Many Union commanders found the idea of fighting side by side with “darkies” unconscionable. Black troops guarded supply wagons, buried the dead, and did “fatigue duty”—any labor that didn’t require them to bear arms. But battlefield segregation gave way to military necessity: The generals needed armed men, even black ones, to kill Confederates. The 23rd fought in some of the bloodiest engagements during the latter part of the Civil War. It took the highest casualties of any unit at the infamous Battle of the Crater at Petersburg. The 23rd entered Richmond after it fell and was present for Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in April 1865.

The church to which the cemetery is attached, St. John the Evangelist Roman Catholic, doesn’t identify George Washington as one of the “notables” interred there. Among the men it celebrates are a U.S. senator from Delaware, Maryland's 29th governor, and "a refugee of the Negro Insurrection of 1791 in the French colony of St. Domingue."

The last of these, Etienne Bellumeau de la Vincendière, apparently never lived in Frederick—he preferred Charleston, South Carolina. His slave-owning family did, however. The Vincendière plantation in Frederick County was noted for a "brutal, Caribbean style of bondage" and "aggressive displays of subjection," Michael E. Ruane wrote in a 2010 Washington Post about the excavation of the family's estate, L'Hermitage.

A resident of the Vincendière home, Jean Payen de Boisneuf, possibly a cousin, is also interred at St. John's. The church's website tells us that he was "one of those who condemned Marie Antoinette to the guillotine." What they don' t tell us is how Boisneuf put his bloody hands to work here during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. "Boisneuf was accused of 'cruelly and immercifully beating and whipping' slaves Harry, Jerry, Abraham, Stephon, Soll and George," reports Ruane. "Two or three negroes crippled with torture have brought legal action against him," wrote a Polish gentleman who visited their plantation, now a National Park Service property, in 1798.

"Members of the family were charged in nine state court cases with cruelty against their slaves, a remarkable occurrence when mistreatment of slaves was commonplace," NPS archaeologist Sara Rivers-Cofield told Ruane. (All charges were dismissed, not surprising for those barbarous times.) File this celebration of enslavers under Brutal Irony.

There's more.

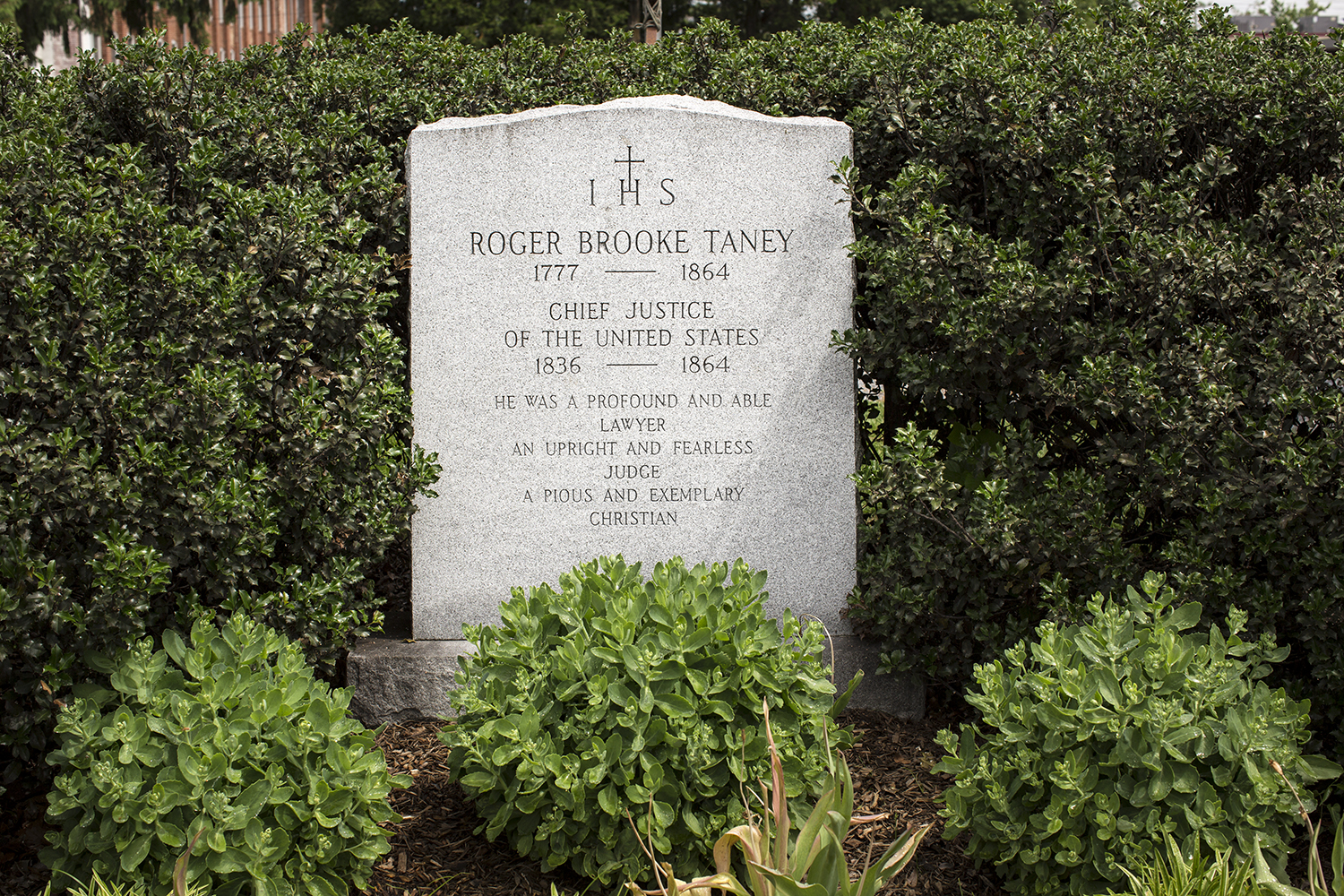

U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Robert Brooke Taney, also a Marylander, has pride of place, both in church history and in the burial ground. (There’s a grander tribute to the judge in his home state: USCGC Taney, a U.S. Coast Guard cutter named for him that was decommissioned in 1986, has been preserved as a “museum ship.” It’s anchored in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Pride of place indeed.)

“Chief Justice Taney is considered by many to be one of the great Chief Justices,” the website says—an interesting description of the man who wrote the 1857 majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which held that men like the Georges “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

That’s the quote people most often pull from Taney’s historic decision, but it’s only the tip of the ideological iceberg on which he floated.

[Blacks] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect, and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic whenever a profit could be made by it. This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race.

In his dissent, Justice Benjamin Robert Curtis, saw past and precedent quite differently:

It has been often asserted that the Constitution was made exclusively by and for the white race. It has already been shown that, in five of the thirteen original States, colored persons then possessed the elective franchise, and were among those by whom the Constitution was ordained and established. If so, it is not true, in point of fact, that the Constitution was made exclusively by the white race.

Curtis’s well-reasoned argument did not hold the day. Prejudice—specifically, the all-consuming desire to preserve the power of Taney’s class to exploit the labor of another class of people—won in our high court. U.S. Senate candidate Abe Lincoln spoke out against the Taney decision two weeks after it was handed down and in his famous “House Divided” speech the following year. Roughly three years later, the Civil War exploded, with this issue at its roots.

Along with my wife, I have written a lot of about how certain strands of our collective American past, in this case the African American ones, have been excised from the stories we tell ourselves as a nation. That’s what Make the Ground Talk, our documentary, is about. People have asked us, politely: Why do the stories you’re telling, about a largely black Virginia community uprooted in 1943 to build a navy base, matter? How can one compare the sagas of nameless, formerly enslaved people like Washington to those of great and powerful men, justices and generals who made decisions and took action of national and international significance?

These are small stories, when considered in isolation. But they are also “small” because we have been taught to regard them as such.

One vital measure of American greatness, which has been applied selectively, is the distance one travels from the proverbial dirt-floored shack to a loftier place where one’s actions and creations benefit many people in society—or earn one mountains of money. What if we applied that measure to the long and brutal struggles of people like the George Washingtons, Harriet Tubman, or Robert Smalls, an enslaved man who commandeered a Confederate ship, steamed it past Rebel defenses into Union hands, and later served five terms in the U.S. Congress? What if we held these journeys toward justice up against the paths trod by great men like Taney, obstructors of justice, champions of enslavement, and beneficiaries of unearned privilege? Or our founding fathers?

For several decades, historians, students, archivists, genealogists have unearthed raw material that has allowed us to reexamine the past and build a better, more honest American history. In George Washington (of Frederick, Maryland), we have such material, tangible and accessible, right in the middle of town, to flesh out the stories that need to be told.